This is the first article in a series about using intelligence for preparedness. I’m starting from square zero in order to introduce a new crop of Americans to the concept of using intelligence, to prove that there’s a need for intelligence and to get readers quickly up to speed on how to incorporate it into their security planning. After getting caught up to speed, if you’d like to read more in-depth and put theory into practice, a book entitled SHTF Intelligence will show you the way forward. You can find a small homework exercise here.

Why do I need intelligence?

You need intelligence because everyone has blind spots. A common theme in the preparedness community is beans, bullets, and band-aids. We need food and water to survive, we need medicine to treat injuries and illness, and we need guns and ammo for defense… but against whom?

In a S***-Hits-The-Fan (SHTF) or survival situation, if we’re dumping hundreds or thousands or more dollars into beans, bullets, and baid-aids, doesn’t it stand to reason that we should investigate our surroundings as well?

I think so. I was a military and contract intelligence analyst, and we in this country are likely to face a lot of the same types of situations that we dealt with in Iraq and Afghanistan. We need to look at:

- Our neighbors and the populace. Are they for us or against us? What are their politics and attitudes? Which households should we approach to build community security in a SHTF situation? Which households will be adversarial to us?

- Key human terrain. Who wields influence in the area? Where do the nearest tradesmen, engineers, and medical professionals live, in case we need their help?

- Known bad guys. Who are the active criminals and gangs in the area? What are their activities, and how can we identify their indicators?

- Future bad guys. Who’s likely to engage in criminality in the future? Which parts of the population are going to resort to criminal behavior in a time of need? Most importantly, in what areas will they be active, and how will they affect my community?

- Law enforcement. How will they respond to a SHTF situation? If they’re going home, as is often assumed, then where do they live and how can we work with them?

- Critical infrastructure. What keeps the world spinning in our area? Do we have critical infrastructure that would invite armed security or suggest an increase in criminal activity? Where can we get the things we need to maintain our survivability?

These are just a few questions that intelligence can answer. At the heart of intelligence is the ability to reduce uncertainty. If you’re concerned about grid-down or financial collapse or the Golden Horde or some other event or threat, then some basic intelligence work should be at the top of your To Do list. Ultimately, what intelligence brings to the table is an ability to make well-informed, time-sensitive decisions.

Colonel John Boyd, an Air Force fighter pilot, was the first to describe the decision-making process he called the OODA Loop. Because fighter pilots have to make split-second decisions, their ability to Observe a development, Orient to what that means, Decide which course of action they should take, and then Act on it is a critical part of their survivability in combat. Similarly, lots of tactical shooting trainers have incorporated the OODA Loop into their curriculum for the exact same reason.

That ability to Observe and Orient is the informational phase of the decision-making process. Can you imagine getting into a gunfight, if you can’t see or hear your opponent? Yet that’s exactly what many are preparing to do on a larger level. We’re limited by our field of vision and line of sight, but with an intelligence effort, we can begin to see well beyond just our line of sight.

So what intelligence allows us to do during a SHTF scenario is not just see our opponent but potentially observe him before a conflict arises. This is called Early Warning, and it’s one of the two key responsibilities of our community security element.

The second major responsibility is producing Threat Intelligence. Knowing that a gang is active in your area is a good first step. We need to move beyond our intuitive approach to information and start using a structured, methodical process to completely remove our blind spots. In essence, we need to graduate from mere information and start producing intelligence.

The difference between information and intelligence is simple: information is raw data, and intelligence is the evaluated, assessed, and synthesized information that answers, “So what?” Hearing that there was a murder in your community is not intelligence; it’s just information. Identifying the perpetrator and his current location, finding out where and why the murder took place, determining how it’s going to affect the community, and compiling it into a consumable product is intelligence.

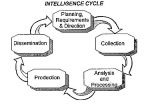

We do this through the Intelligence Cycle. There are five phases, and I’ll briefly detail them in order. In Phase One, we understand our mission, assign analytic tasks and responsibilities, and begin generating our intelligence requirements (covered in the next section). In Phase Two, we task those requirements out for collection. Once that information is collected and reported, we start with Phase Three, where we analyze the incoming information. After filtering out the bad information and analyzing the good information, we produce the actual intelligence. We provide predictive intelligence, which is describing what might or is likely to happen in the future, or estimative intelligence, which is describing an organization’s strength and capabilities. Finally, once we produce the intelligence, we need to ensure that it gets into the hands of the right people. In Phase Five, we disseminate the intelligence to our leadership, our community security team, or the community at large.

Let’s start with Phase One. We need to generate some intelligence requirements or, in other words, statements or questions that describe intelligence gaps.

Let’s say that you do have a gang in the area. What don’t we know about that gang but need to? Do we know how many members are associated with the gang? Do we know where those gang members hang out? Do we know where those gangs are criminally active? Do we know if certain areas are at a higher risk than others (and have we mapped out those areas)? There are potentially lots of intelligence gaps we have, especially if we expect them to be active in a SHTF scenario.

So we can take these questions and start a list:

- How many members are in the Leroy Jenkins Gang?

- What are the known hangout spots for Leroy Jenkins Gang members?

- Identify all high-risk areas for Leroy Jenkins Gang activity.

- Et cetera…

If we’re building a house, or in our case an intelligence product, then this list of requirements represents our building materials. This is all the information– the lumber, nails, bolts, roofing shingles, doors, and windows– we need to finish our intelligence estimate. Without knowing what we need, we won’t build a very good house.

And thus ends lesson one. Head on over to our homework page for a practical exercise. I’ve also posted a video that will step you through the process of analyzing your community from multiple angles.

Samuel Culper is the Executive Editor of Forward Observer Magazine