(Continued from Part 2. This concludes the article.)

Early in the season, in this same spot, I learned that I was truly a hunter. It was not when I took my deer because I took him from another place on our land. Instead, it was when I passed up an immature buck. That spike I mentioned earlier gave me multiple opportunities to shoot. I never did. Knowing that I had the discipline to stick with what I had deemed a mature animal gave me the confidence to continue hunting the big bucks. I knew, without a shadow of a doubt, that even if I saw a monster, I would not shoot unless I was sure that my shot could be placed properly.

I will not attempt to explain every encounter with deer I had during my first season, but I will attempt to give some pointers to those looking for big bucks. Big bucks are tricky. John Wooters called it right when he wrote in Peterson’s Hunting 1987, “A mature Whitetail buck is the easiest animal on the face of the earth to underestimate. He’s capable of things the average hunter simply refuses to believe. The more credit you give him for wiliness…and for wariness…the closer you are to the truth-and to collecting his scalp. And the less credit he gets, the better he likes it. Like old Lucifer, he prospers most when no one believes in him.”

It is often assumed that big bucks only like thick areas, but this is not always the case. I have seen more buck sign in edges between types of woods more than any other place. A good portion of our property is swamp during the deer season. Thick as the devil. I have never seen a big buck in this area thick as it may be.

Big bucks also out-smart hunters by the time they are moving. One morning as I was heading out, I was foiled by a buck who was in replanted pine. That is the clearest area on our land, but he knew he was safe because of the time.

On another occasion, I heard a buck move out of the swamp just after sundown heading towards drier area to bed down. I was hunting at the same place when a buck moved out of a different area of the swamp and bedded down just far enough away to be out of the water. He bedded down 5 to 10 yards from where I was sitting. Both of the two previous instances happened just at the end of legal shooting time.

So when do bucks move during legal shooting time? I am not entirely sure. The rut changes the habits of all deer, but it seems that as more and more hunters pressure the deer during the season, the deer adapt to move at times no one believes them to be moving. This is during the mid-day hours.

I shot my buck at midday in the same place where I had missed a chance at those two who ventured out just after shooting time. He could have been one or both of those deer, but I cannot be sure.

I had been hunting early that morning in a slow, misting rain and had seen nothing. Deciding to re-strategize, I came home and oiled my rifle and sidearm. Later that morning, I headed back out around 11 o’clock. Although I had not been in position as long as normal, by 12:50 I was ready to call it a day. To be honest, sitting in one place for three hours at a time on so many previous days during the season was wearing on me. As I mentioned earlier, always remain at your post until your previously designated time. I had decided to stay until 1:00, and that was what I would do.

I cannot tell at exactly what time it happened, but off to my right, some movement caught my eye. It was a buck, but I could not tell how large. Before I shot, I wanted to see two things: the spread of his antlers and the length of his brow tines. From the angle he was walking, I could not see either. He was walking steadily toward some heavy brush, and I knew that I would miss a shot entirely if I didn’t shoot quickly. Jack O’Connor said, “The big ones always look big.” This buck looked big, but he was moving.

I have never had any opportunity to practice for moving targets. I remembered something I had read which said to grunt like a goat to stop a deer without alarming it. I tried that, but I was too scared of spooking him to make any audible sound.

As he stepped from behind a group of three pine trees, I made the final decision to fire. First came antlers, then head, neck, and shoulder. I cannot explain exactly where I placed my crosshairs, but I can still see them finding their mark. With the safety of my rifle already off, I squeezed the trigger, but it was not the report of the rifle that I heard, nor the bullet finding his lungs. Instead, I heard only his hoofs hitting the ground as he took off at full steam ahead.

This was the point when I knew the hours of training paid off. Before the buck had gone ten yards I had another round chambered and ready. Although I could no longer see him, I heard what sounded to be the buck collapsing into the dead leaves of autumn.

I waited a few seconds after all was quiet then proceeded to the place where I shot the deer. At this point, I should have stayed back at my post and waited for the rush of adrenaline to settle before moving, but excitement overrode reason. Thankfully, I did retain enough of my composure to keep myself from running into the thick woods where I thought the buck to be.

With any game animal that is possibly wounded it is crucial to give him enough time to bed down and expire. Thirty minutes is the rule of thumb.

I returned to my house in order to get my dad’s help in tracking my deer. Neither of us had any previous experience in tracking game, but two sets of eyes are better than one. We returned to the spot about twenty minutes after I had shot the deer. I was the first to spot sign. What first caught my eye were fresh deer droppings. A couple of feet from them was a spot of blood and hair. I knew I had made contact. It was clear in the minutes that followed that the deer had been hit hard and was bleeding fast. We tracked him into the thick brush where the trail got to be a little squirrelly.

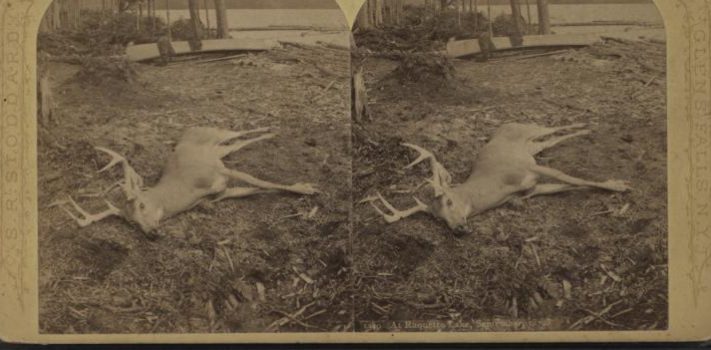

The deer had run directly under a sweetgum tree which was dropping blood-red leaves. Needless to say, that made a blood trail hard to follow. I was more than thankful for the extra set of eyes. My dad was able to pick apart the contrast between blood and leaves better than I. We tracked him into brown leaves, but didn’t get very far before I saw him lying on the ground.

I handed my rifle to my dad and advanced making a swift move for the Smith and Wesson 27 sitting cross draw on my left hip. I was prepared to give him a coup de grace if necessary. It was not. Earlier when I thought I heard him collapse, I had indeed heard correctly.

From this point on, it was no longer my study that paid off, but good friends who were willing to help. These friends have been hunting as a means of sustenance for longer than I have been alive. Field dressing, quartering, and butchering are all quite simple, but it takes someone who truly knows the right method to teach others.

Although quartering is quite simple, the crucial part comes between quartering and butchering. Do not put your deer in a big refrigerator as those who butcher deer for a living. Instead, take the quarters and put them in large coolers packed with ice. Every day open the drain plug and let any water run out. Then, replenish with more ice. Do this for a week to ten days. If you are concerned about the meat tasting “gamey” include vinegar a couple of times. When the time came to butcher my deer, all the wet-goat smell was completely gone.

After having eaten this meat over the past months following the season, I can say it is the best tasting meat I have ever had. Although I shot a big buck, the meat is not tough in the least.

Although many would probably fault me for this, I did not continue hunting after taking that deer. It was not that I was afraid to kill another, but that I wanted to leave the woods well-stocked of Nature’s Bounty in case the supposed TEOTWAWKI came. I am unapologetically a staunch conservationist. I also chose to stop hunting at that time because I was pleased with what I had learned, and I was ready to hunt again after more study and scouting.

In conclusion, I hope this article served to do more than just allow me to tell the story of a first deer. I hope it motivated those who have never hunted to give it a try, or those who stopped many years ago to take up the chase once again. The joys of being alone in the woods are numerous. As John Madson said, “When you go into the woods your presence makes a splash, and the ripples of your arrival spread like circles in water. Long after you have stopped moving, your presence widens in rings through the woods. After a while this fades, and the pool of silence is tranquil again. You are either forgotten or accepted-you are never sure which. Your presence has been absorbed into the pattern of things, you have begun to be part of it, and this is when the learning begins.” I cannot think of an activity that puts you in the place Madson described above more than hunting.