I think that the biggest gap and blind spot that we have in preparedness circles is training. A quick look at social media will confirm this. You’ll find discussions and photos of all the latest whiz-bang gadgetry we buy, photos of our food stockpiles, photos of guns and ammo, but not a lot of discussion on the training we do. Now, I‘m not really a fan of discussing anything on social media, which I’ll get into in a second, but most people narrative their lives on it, and the lack of discussion is proof that training isn’t happening for most.

The main reason to avoid social media discussions is Operational Security (OPSEC). The DHS has publicly stated that they believe preparedness to be an indicator of “potential right wing domestic violent extremism”, right alongside “a strong belief in the Constitution”. Yes, really. Not only is being flagged by the DHS a concern, but the Defense Production Act is as well. In an emergency, the local FEMA director can declare an item as “critical” and therefore declare anyone keeping more than “immediate personal use” quantities to be “hoarding” in violation of 50 USC 4512. This allows them to arrest you and seize whatever you have, whether it be food, ammunition, gasoline, GPS units, radios, etc.

It’s important to know that the DPA lists “any item on the International Trafficking in Arms Regulation (ITAR)” as automatically authorized for a “critical” designation. What’s on that list? Well, aside from actual arms and ammunition, anything used militarily is listed. Things we don’t normally consider “arms” but are. GPS receivers, compasses, optics (night observation and rifle scopes), radios, and anything else that can be used by a military force. In other words, most things that we in the preparedness community gather and stockpile. It will do no one any good for your stuff to seized on Day 12, because you had a viral post about your “hidden wall of cans”.

But, to get back to our original point, it’s one thing to amass a mountain of gear and supplies, but it’s quite another to actually get out and know how to use that gear. As sad as it is, a good-sized portion of those who call themselves ‘preppers’ haven’t even tried living outdoors for 3 days, let alone making a two-week trek on foot, carrying enough gear to 14 days.

Let’s start there. We live in our climate-controlled houses, drive our climate-controlled cars to either our climate-controlled workplaces or climate-controlled stores and back again. We live our lives in a bubble of 65-70 degrees. For most people, if you vary that by 5 degrees, they are either very cold or very warm. You need to begin acclimating your body to variations in temperature. For example, I live in Michigan. Most people in Michigan have lost their cold tolerance completely. I get strange looks because I refuse to wear a coat at all until the temperature gets below 30 degrees. Then I wear a light jacket until it gets below 20. I don’t put on a heavy parka until its under 10 degrees. By living this way, I’ve retained my tolerance for cold, in the event that I need it.

When I bring this up with people who claim to be “prepared”, they say things like “Well, I’ll wear shorts and a T-shirt” if it gets too hot. If you are living in a collapsed society/Without Rule of Law (WROL) environment, shorts and short sleeves will lead to cuts and bites, which will lead to infections. Without a functioning medical system, an infected insect bite can (and will) kill you.

So, we begin our training by learning to acclimate ourselves to being outdoors and in the weather. It seems like a no-brainer to most of us, but many have never considered it.

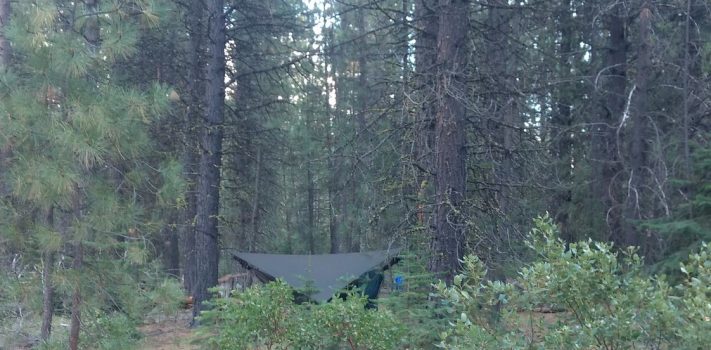

Next, you need a regimen to develop outdoor skills, but not just “camping”. We need to remove that from our lexicon because it denotes a large campfire, people sitting around singing, and generally having a good time. Camping out in the wilderness during a collapse will not be anything like that. You will need your fires out be dark, you will need to select concealed campsites, and operate as quietly as possible.

I have a suggested training regimen for people and groups to begin getting more realistic in their training, and it allows them to learn more about their gear, and what does or does not work. The time to realize that your sleeping bag is inadequate is not on Day 4 of a societal collapse.

The first skill and ability we need to work on is the ability to cover distances on foot while carrying a load. Again, it seems like a no-brainer, but putting on your backpack and walking around your yard to “see how it feels” is very different than moving 15 miles over rough terrain, while trying to avoid contact, wearing the backpack.

Start small. If you aren’t active at all, spend the first week just walking, getting your body used to moving. The next week, add your backpack with a little weight. A lot of you will recognize this as the new fitness craze of “rucking” among veterans, but we are going to do it slightly differently. Those who are into rucking for fitness, do it with actual weights and are going for speed. We’re going to do it by packing our ruck with actual field gear, and we’re going to be more concerned with quiet movement than we are with speed.

A good drill, once you’ve gotten used to carrying the weight, is what I call the “lunch test”. When packing your ruck, put some of your portable survival food and a way to cook it in your ruck. This could backpacking food, MRE’s, canned food, or whatever you plan on actually using. This is vital because if you’ve never used an MRE heater or never prepared a Mountain House packet, you don’t want to be making rookie mistakes when your life is on the line. Hike out for one hour. Find yourself a covered and concealed spot to take your “lunch break”. Take out only the items you intend to use (stove/food/water). Get in the habit of stashing your ruck in a camouflaged spot while you are eating. In a real WROL/Collapse situation, you may need to run, and come back to it later. Prepare and eat the lunch, and then sterilize the site, making it appear that you were never there. Retrieve the ruck and walk the hour back out.

Now, you’ve established some habits, you’ve learned that you can do it, and have developed a little confidence. Do this at least once a month, in all weather conditions. Yes, in the rain and snow, too. The Collapse won’t happen only on sunny spring days. Acclimate yourself to being uncomfortable.

After you have this under your belt, work on the “Overnight Test”. Select a campsite that will require 4-5 hours of hiking to get to from a parking spot. This is to enable you to practice movement skills and to prevent you from deciding to just go back to the car if things don’t go well. Get out, gear up, throw on the ruck, and begin stealthy movement from your car to the campsite. Once you get there, remember our purpose: training, not camping.

Run the site like you would in a collapse environment. Don’t set up your tent or tarp and sleeping system until the last possible moment. Ensure that any cooking fires are done and out before dark. Only take out of your ruck things that you are using right now. Keep the camp low-profile and camouflaged. In the morning, rise before first light and take down and stow your sleeping system and tarp/tent first, just like you would do in a tactical environment.

After your gear is stowed, make your breakfast, perform self-administration like hygiene and brushing teeth/changing clothes, etc. Then, just before leaving, sterilize the site, removing any large traces of your presence.

The next step in your training progression is then to do a “weekend test”, where you combine these. First, you start exactly like the “overnight test”. In the morning, you then hike out a few hours, and stop for lunch, essential conducting the “lunch test” process. Then, hike a few more hours to your second overnight site. In the morning, hike back to the car, stopping again with another “lunch test” on the way.

As you can see, this will start acclimating you to life in a collapse. It’s important that you actually change locations each night. Staying in the same spot in a tactical environment increases the chance that someone will find you. Even in the US military, they generally don’t occupy one “patrol base” or overnight site for more than 24 hours. Get in the habit of moving.

With a group, you can do all of the same things, but add in group dynamics. For example, every time you eat, half the group eats while half man the perimeter, then switch. Assign security roles overnight. Practice movement formations while moving. It can be a fun and revealing event.

Now, once when I suggested these skills in a group on social media, one guy replied “Look, I want to be prepared, but I have no desire to play soldier”. That’s a fine attitude to have, but what if the other side decides that “Soldier” is the game that you are playing? Many seem to have this mistaken belief that you could just live out your entire existence after a collapse in some type of Little House on the Prairie cosplay, but reality is that even the most remote bug out location may get overrun and you need to at least have the skills to enable you to survive and deal with that.

Even living your ideal life on the prairie is going to eventually require you to leave the house. If you want to be safe, you need to at least conduct local patrolling, and these skills will help you with that.

I like to compare it to frontier living in the US. The pioneers were families and farmers, but they were ready to be warriors when called upon. Families would all fort up and then band together to put an armed force in the field to deal with whatever threat came their way. That should be our goal.

Don’t just be a gear collector. Get out and actually train with every piece of gear you have, and do so in actual field conditions. It may help you realize that most of the latest whiz-bang gadgets that we spend our money on are junk with no real-world purpose or practicality.

Get training, friends.

About The Author: Joe Doilo is the author several books on field training and tactics, including: Fieldcraft: TW-02 (Tactical Wisdom).