“There is but one step from all this sense of irresponsibility and self-separation from city government—and I believe this is the very road which is taken—to that deep pit of fallen citizenship into which men plunge who bribe their way through city government to what they want. These men commit the unpardonable sin of city life. I know of nothing in all the range of municipal reform more important than the tearing up by the roots of the infamous practices of bribery. There is no worse citizen in America than the good citizen who pays a bribe. He is as much worse than the man he bribes as his social and financial opportunities are greater and his temptation less. His crime is committed without necessity and without haste. It is cold-blooded, mercenary debauchery, and wholly inexcusable. It inevitably must be stopped. It furnishes food for the greater part of the corruption of city government; with the spoils system it furnishes nearly all; and it is impossible to reform city government as long as this horrible vice in its present virulence exists. It is not only a grand obstacle to the introduction of business methods in city government, and it is not only immoral, dishonest and dishonorable as scarcely anything else in the corruption of city life is, but, upon the part of the bribers, is scandalously mean and degraded, in view of their chances in the honorable competition of business life and of the absence of all serious temptation.

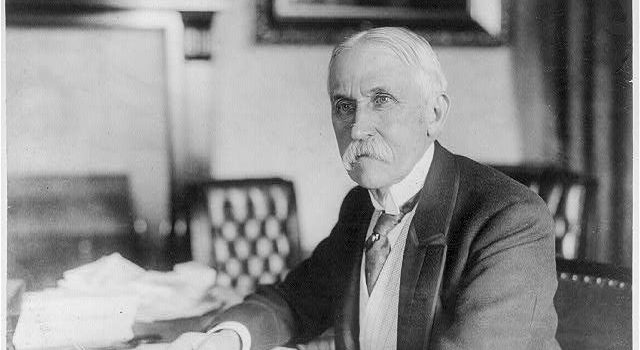

As I believe the uprooting of these practices to be of the greatest moment to municipal reform, I beg to offer the practical suggestion that a change might be made in the laws punishing the crime. We have tried without avail laws making both briber and bribed equally punishable, because, as both are liable to punishment, both have the highest motive for secrecy—and evidence can hardly ever be obtained. We have also tried making the bribed alone punishable; and this has not availed because the briber is usually a man of too much position to be willing to tell the truth and appear in his true light. He is of that higher grade of criminals which can be trusted to believe in honor among thieves. I suggest the remaining alternative of making punishment apply only to the briber, for though the bribed would not always peach, he is of the sort that certainly sometimes would; and the briber, knowing the grade of man he was dealing with, would always regard him as a man who might; and would be apprehensive that when exposure did not follow, blackmail would; all of which would add new risks that very few monied men would dare to take. Moreover, in city government bribery there are usually so many of the bribed that the risks of exposure or blackmail would be immensely multiplied.” – Treasury Secretary Franklin MacVeagh (November 22, 1837 – July 6, 1934)