There are many folks who know much more than I do about Signals Intelligence (SIGINT). A quick check at YouTube, or Internet sites will bring in tons of data if you wish to; my effort in this article is aimed at the individual who simply wants to know who is still broadcasting and know that they are not the only person(s) wondering if humanity has been wiped out.

Imagine that there has been some apocalyptic event. It might be a solar storm event on the scale of the Carrington Event of 1859 where Earth was hit with a large X-Class solar flare which caused a lot of confusion. Imagine if such a large scale event took place today in our modern world of electronic presence. Imagine the world without most forms of electronic communications. Or it might be a nuclear attack on the Continental United States (CONUS) that would have the same effect as a solar flare, and much worse could spread radioactive fallout around the northern hemisphere. Just knowing that there were others that are still alive and able to send out any form of radio signal would at the very least be a morale booster to know that there are fellow human survivors. But are your fellow survivors good people, or is there a possibility that they would be a serious threat to you and your family, to your friends?

The goal of this article is to pass on some ideas of how you would be able to seek out and detect signals to be able to use them for making decisions that can enhance the safety of your family or group. One goal in SIGINT collection is not transmitting any signals that may give away your location until you are ready to send out signals. SIGINT is a “receive-only” activity. Thus, this is a passive activity that can keep you safe.

There are many forms of communications ranging from simple continuous wave (CW) Morse Code to complex data signals, or from sources ranging from satellite data to beacon data stations located around the globe. One such source detected from 1976 to 1989 was the “woodpecker” signal being emitted by the Russian over-the-horizon radar located in Siberia. It was directed toward North America. Most owners of High Frequency (HF) radios heard this signal very clearly whenever the Russians were transmitting it, across an annoyingly wide range of frequencies. There is also a plethora of HF amateur (“ham”) traffic, and international broadcasts.

What if you don’t have a ham radio? Or what if you do, but you cannot transmit with it because you didn’t get your ham license? One does not need to have ham license to listen in across the radio spectrum, now and after The End Of The World As We Know It (TEOTWAWKI).

I do recommend getting at least the Technician level license, if nothing more than to be able to train on and use whatever radio transceiver equipment you happen to have on hand. Owning gear but not practicing with it is foolish. Just like the folks who buy a ferrocerium rod and never practice using it to start a fire. You should be able to do this on a dry day or in a winter snowstorm.

Practice makes perfect, and to that end I have bought several types of radio equipment to search out and use the detection of signals being transmitted to make assessment of what may be going on around our Area of Operations (AO). In his novel Survivors, the author James Rawles wrote about a fictitious veteran making his way back home and communicating via low-power CW Morse Code signals.

Even if all one did was to interrupt the normal noise that is heard as static on a radio using Morse Code or some kind of prearranged code, the message could be sent and received. Early experiments in this form of communications were called spark gap transmissions. A source of electromagnetic field was generated and then disrupted causing a huge spark of static electricity to jump the gap of the transmitter coil. The first such transmission was sent by Marconi across the Atlantic Ocean and was the beginning of what we now know as ham radio as well as modern communications.

The most popular form of a beginning signal intelligence gathering operation is most likely something you already have: a simple radio. The AM (Amplitude Modulation) radio is the best for long-range listening that could be worldwide in range, while FM (Frequency Modulation) is good for short distance listening usually a distance of maybe a hundred miles or so but very clear assuming that the radio station is up and running according to their power level and antenna signal strength.

The Classic Transoceanic

One of my favorite radios I have, amongst the many that seem to have found their way to my lair, is a Zenith Transoceanic Shortwave Radio (SW) that was built in 1946 just after WWII. These types of radios were the first of the so-called portable radios that were made popular in the mid-1930s up to the mid-1950s when they were supplanted by transistor radios. The earlier radios were heavy by comparison to the newer radios that used transistors. Most of them, like my set, weighed in at 15 pounds or more with the A-type and B-type batteries installed. They also had the ability to use AC power from the grid. That was something that was novel in many parts of the USA and most of the world.

The vacuum tubes in the Zenith Transoceanic set used mainly one volt for the filaments, and when plugged into the grid power had a special tube that regulated the current down to a level the tubes could use to drive them even though the grid was notorious for voltage and current fluctuations which would burn out the tubes if not properly regulated.

The batteries were good for about 25 to 40 hours of use until they died. Once they died one simply bought new ones and went on listening to the favorite evening show or music; even from as far away as Europe, South America, and all around the world at all hours of the day or night. (Although the best listening was at night.) Modern SW radios, on the other hand, can weigh less than a pound, and can use rechargeable batteries. They can also receive transmissions from all around the world as their distant relatives of the tube era.

I like the rich tones from my Zenith Transoceanic radio and the fact that in the event of an X-Class solar flare or Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) event, the tubes won’t fry as easily as the modern transistors and integrated circuit (IC) chips will. If one takes reasonable precautions, I believe most tube-type radios will survive, a simple Faraday storage solution could be made to shield the radio from such pulses. Of course, transistor radios will need such precautions as well and it would be wise to do so while there are no such events going on.

SDR Technology

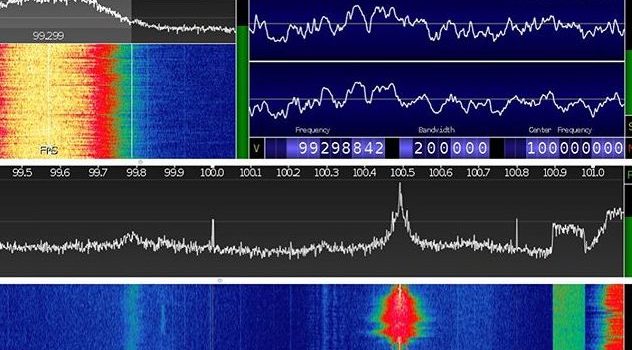

One level up from a simple everyday compact shortwave radio could be the Software Defined Radio (SDR) receiver. This is a radio that is developed around a receiver circuit that is driven by software programming. Here is a link to some SDR units ranging from $40 up to $450 and even higher if one looks at the FLEX line of radios:

Here is a link to some typical SDR dongle type radios.

Flex line of radios starting at around $3,000 and up. The Flex line of radios is a serious investment in not just a receiver that can quite literally listen in on the world, but transmit as well so this would be a topic for a different article, maybe someday I’ll be able to do a product report on one. “Dear Santa…”

(To be concluded tomorrow, in Part 2.)