Recently, I have been working with a couple of old Smith and Wesson top-break revolvers. One is an exposed hammer Double Action Second Model from about 1882. The other is a Safety Hammerless Fifth Model from about 1940. Both are chambered in .38 S&W.

The original .38 S&W cartridge was designed for black powder. When it was first loaded with smokeless powder, the loads were light, intended to be used in firearms designed for black powder pressures.

Later on, from 1922 to 1963, the British armed forces adopted a version of the .38 S&W cartridge as their standard revolver cartridge. This later version, designed for sturdier Webley and Enfield revolvers, was significantly more powerful than the earlier version that had been developed in the late 1800s.

The old top breaks that I have been working with were not designed to withstand the pressures generated by the more powerful later cartridges. It was important to find some “kinder and gentler” ammo for them.

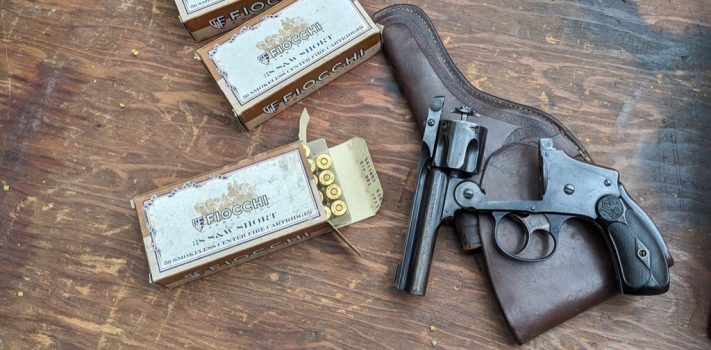

I contacted Fiocchi for help, and they were kind enough to provide me with some of their “Cowboy Action” 145-grain lead round nose (LRN) ammunition. The ammo proved to be clean, consistent, and (most importantly) did not damage the revolvers or the person firing them.

If you pick up an antique centerfire handgun from the Elk Creek Company, through Gunbroker, or elsewhere, I recommend that you seriously consider Fiocchi “Cowboy Action” ammo as the fodder of choice for your new acquisition.

The Double Action Second Model

The revolver is nickel plated, but after more than 140 years of use, the finish is beginning to wear off in places. There is a Smith and Wesson seal on the right side of the frame of the revolver above the grip.

There are 5 chambers in the cylinder. Since the firing pin is an integral part of the hammer, those who use this revolver would be wise to have an empty chamber under the hammer while carrying. This would prevent an accidental discharge in the event that the revolver was dropped, or that the hammer was struck in some other manner. With a 3-1/4-inch barrel, the revolver is quite light by modern standards, and extremely well-balanced. The rifling in the barrel is still good.

There are 5 chambers in the cylinder. Since the firing pin is an integral part of the hammer, those who use this revolver would be wise to have an empty chamber under the hammer while carrying. This would prevent an accidental discharge in the event that the revolver was dropped, or that the hammer was struck in some other manner. With a 3-1/4-inch barrel, the revolver is quite light by modern standards, and extremely well-balanced. The rifling in the barrel is still good.

The Safety Hammerless

This revolver is blued, with the finish beginning to wear off near the end of the barrel on the left side.

The design is quite similar to that of the Double Action, with the exception that the hammer is hidden within the frame, and the revolver includes an integral grip safety. The Safety Hammerless also feels slightly heavier, as if it were milled with somewhat more substantial parts. The double action trigger of the Safety Hammerless has a somewhat heavy and long pull, but breaks very crisply. It has a 3.5 inch barrel, which is still shiny with no pitting.

The design is quite similar to that of the Double Action, with the exception that the hammer is hidden within the frame, and the revolver includes an integral grip safety. The Safety Hammerless also feels slightly heavier, as if it were milled with somewhat more substantial parts. The double action trigger of the Safety Hammerless has a somewhat heavy and long pull, but breaks very crisply. It has a 3.5 inch barrel, which is still shiny with no pitting.

Testing

It was a cool, grey afternoon in late June, with scattered showers and gusting winds. The temperature was 62 degrees Fahrenheit, and humidity was close to 100 percent. I made my way to the improvised range behind my pole barn, and set up a target stand in front of the back stop. I then set up a table 15 yards away with a pistol rest on it.

It was a cool, grey afternoon in late June, with scattered showers and gusting winds. The temperature was 62 degrees Fahrenheit, and humidity was close to 100 percent. I made my way to the improvised range behind my pole barn, and set up a target stand in front of the back stop. I then set up a table 15 yards away with a pistol rest on it.

During some previous function testing, I had not been satisfied with the timing of the double-action revolver. As a result, I only used the safety hammerless in this range session.

I loaded a single round of Fiocchi “Cowboy Action” 145-grain LRN into the safety hammerless revolver. I then placed the revolver in the rest, aimed at the center target, and fired.

I needed to pull the trigger with my middle finger, since I had recently bruised the index finger of my right hand while moving furniture. Our church facility is currently undergoing a number of renovations, and I helped to empty the offices to allow for repainting and the installation of new carpet.

It was difficult to find a good place to keep my index finger while pulling the trigger with my middle finger. While firing this first round, I had my index finger against the frame of the revolver under the cylinder. Enough hot gasses leaked out between the cylinder and the barrel to leave a black smudge on my finger. This was not unduly uncomfortable, but I decided to place my finger in a safer location in the future.

The first shot struck about 13 inches above of the point of aim. The fact that the point of impact was so far above the point of aim was an important lesson for me. When testing an antique handgun, it may be wise to begin at 5 yards rather than 15, and then move back if appropriate.

I moved the shooting table up to the 5-yard mark, loaded the revolver, and fired a 5-shot group. The group was not too bad all things considered, at about 1.2 inches in size. But it was about 5.5 inches above my point of aim.

An examination of the front sight of the revolver revealed why it was shooting so high. A previous owner had filed down the front sight quite aggressively. Perhaps that owner had a pronounced upward flinch to compensate for. Perhaps he fancied himself as a quick draw artist, and did not want the front sight snagging on anything as he drew. Perhaps the front sight became damaged at some point and a previous owner filed it smooth to hide the damage. Whatever the reason, I now knew that I needed to aim this particular revolver quite low.

After firing a number of groups from rest, I switched to firing off-hand. I began to get a feel for the best Kentucky windage to use to compensate for the shortened front sight. I was pleased when my final five-shot group clustered respectably near the center of my intended target.

About this time, the intermittent rain was beginning to spit and threaten worse to come. I packed things up and headed for shelter.

Advantages of Antique Firearms

One nice thing about antique firearms is their historic interest. It is fun to own guns that have been around the block a time or two, and have played roles in the great drama of the past. A second advantage of antique guns manufactured in 1898 or before is that they are not considered “firearms” under the terms of the Gun Control Act of 1968. As non-firearms, they can be sold across state lines without the assistance of an FFL or an FBI background check, and can be shipped via the US Postal Service. (State laws vary widely, but there are no Federal restrictions.) Sometimes it is nice to purchase a gun without jumping through a bunch of hoops.

It is important to note that state and local laws may be more stringent than federal law in regard to antique firearms. For example, some states only consider a firearm to be an antique is it not only was manufactured in 1898 or before, but is also chambered for a cartridge “for which ammunition is no longer manufactured in the United States and is not readily available in the ordinary channels of commercial trade.” It is wise to be aware of your state and local laws as you plan your antique firearm purchases.

Bad Company

I am sorry to report that revolvers originally chambered in .38 S&W have been misused by some especially unsavory characters. These are presidential assassins and would-be presidential assassins.

This misuse began on July 2, 1881, when Charles Guiteau shot President James Garfield with a revolver chambered in .38 S&W. President Garfield lingered for 80 days following the shooting, but ultimately succumbed to infection.

Then on October 13, 1912, John Schrank shot Teddy Roosevelt. Schrank was also using a revolver chambered in .38 S&W. The bullet passed through Roosevelt’s extensive notes for his speech as well as his glasses case before lodging in his chest. Roosevelt proceeded to deliver his speech on schedule even before seeking medical attention. Because of the bullet’s proximity to Roosevelt’s heart, the bullet was not removed, but remained in his chest for the remainder of his life.

Finally, on November 22, 1963, Lee Harvey Oswald had an encounter with Dallas Police Officer J.D. Tippit. Tippit attempted to interview Oswald as a possible suspect in the shooting earlier in the day of President John F. Kennedy. Oswald drew a Smith and Wesson Victory pistol from his pocket, and fired at Tippit five times, striking him three times in the chest and once in the head, killing him. The Victory pistol had been originally chambered in .38 S&W. It had then been rechambered in .38 Special, but not re-barreled. So Tippit was killed by .38 Special bullets fired through a slightly larger bore diameter .38 S&W barrel.

Conclusions

Fiocchi “Cowboy Action” ammo is an excellent choice for the potentially delicate actions of antique handguns. The Fiocchi ammo is clean, consistent, and operates well within the tolerances of older firearms. I highly recommend it.

Disclaimer

Fiocchi was kind enough to provide me with several boxes of their “Cowboy Action” ammo in .38 S&W. I tried not to let their kindness interfere with my objectivity in this review, and believe that I have succeeded. I did not receive any other financial or other inducement to mention any vendor, product, or service in this article.