One of the most common questions asked by new preppers is “What should I prepare for?”. The easy…and wrong…answer is “everything”. After all, as Frederick the Great said, “He who defends everything, defends nothing”. If one attempts to prepare for everything that can happen…from coastal erosion to Electro-Magnetic Pulse (EMP) to winter weather…one could quickly become overwhelmed. This is why the first steps in preparing should be to assess and prioritize risk.

For background purposes, I spent more than 25 years as a commissioned officer in the United States Army Reserve, including multiple deployments. When planning military training and operations, a formal risk assessment is always a requirement. In addition, I hold a Master of Arts in Emergency and Disaster Management, and I currently work in emergency management, where assessing risk is a significant part of my duties. I say this not to boast, but to offer the reader the context from which I approach this subject, as well as to maximize transparency to the greatest extent possible while maintaining a reasonable level of Operational Security.

Risk is an inherent part of life. Regardless of where one lives, or what one does, we all assume a certain level of risk every day. What is key is developing an accurate assessment of what risks one actually faces, in order to better mitigate and prepare for those risks. And no, mitigation and preparation are not the same thing, although there is certainly some overlap. In short, mitigation includes steps taken to reduce the impact of an event when it occurs, while preparation includes steps taken to respond to an event after it occurs. For example, if one buys a tarp, tape, and nails to cover any windows that might be broken during a windstorm, that’s preparation. If one puts plywood over the windows to reduce the chances of breakage during a windstorm, that’s mitigation.

Purchasing a generator to provide continuity of power during an outage could be considered both mitigation (since it reduces the impact of the power loss) and preparation (since it is engaged as part of the response to the event). Regardless, in order to better focus limited resources when developing mitigation and preparation measures, it is necessary to accurately identify potential hazards, assess risk, and then utilize that analysis to maximize effects in planning.

Hazard Identification

The first step in assessing risk is to identify what threats or hazards are actually viable in a particular area. Hazards are normally divided into three categories, natural, human-caused, and technological. A natural hazard is something that occurs in God’s Creation, such as hurricanes, tornadoes, or lightning. A human-caused hazard is something created by people, either by malice or negligence, such as a terrorist attack, nuclear strike, or hazardous material release. Finally, a technological hazard is something that occurs due to a failure of technology, such as a dam failure or cyber-attack.

Note that there may be overlap in some of these areas. For example, a Geo-Magnetic Disturbance (GMD) occurring from a Coronal Mass Ejection, similar to the Carrington Event of 1859, striking the Earth would be a natural event. The effects on technology, however, would create cascading technological failures, such as disruptions and degradations in power distribution and telecommunications, which could lead to failures in life support systems, sanitation systems, fuel distribution systems, etc. A wildfire may be the result of a lightning strike, making it a natural hazard; or it may be due to the negligence or malice of a person, making it a human-caused hazard.

It should be noted that hazard identification is not based merely on past occurrences; just because something has not happened in the past does not mean it will not happen. The purpose of hazard identification is to identify potential hazards, as well as eliminating those that will not occur. For example, I live in an East Coast Southern State. Hurricanes are absolutely a hazard. Winter weather, although rare, does still occur. An attack by Godzilla, however, is completely impossible, since those only happen in the Pacific. Okay, bad example…sandstorms, volcanic activity, and geyser explosions, however, are impossible, as direct hazards at least, in my area. Therefore, start by identifying those potential hazards…natural, man-caused, or technological…and eliminate the impossible.

Risk Assessment Process

This leads directly into assessing risk. Risk is generally composed of two factors: probability and impact. Probability is simply the likelihood of something happening. For example, where I live, hurricanes are fairly likely, as they occur nearly every year. Winter weather, on the other hand, is fairly unlikely, though not impossible. Impact represents the effect that such an occurrence would have on those in the affected, and in some cases, adjacent, areas. This can include deaths, injuries, dollar amounts in damage, families displaced, etc.

A comparison of probability and impact can help to identify which hazards pose the greatest risk. For example, an event with a high probability and high impact…such as a hurricane…would be rated at a high risk. Something with a low probability and low impact…such as a tsunami in an area not immediately adjacent to the coastline…would be rated as a low risk. Items with a high probability but low impact…such as hail…or items with a low probably but high impact…such as the aforementioned GMD…would fall somewhere in between.

It should be noted that impact should include cascading effects, as well as direct effects. For example, in the aforementioned tsunami, an area not immediately on the coast may not suffer a direct effect of the tsunami; however, cascading effects, such as power outages and supply chain disruptions, should also be considered as well.

Scoring these items would allow one to more accurately assess the risk of specific hazards in one’s area, then compare them in order to better determine what preparation and mitigation measures should be developed. For example, assigning a numerical score between 1-10 for both probability and impact to each hazard would allow one to average those scores together to reach an estimate of risk. If one assigns a probability score of 9 and an impact score of 6 to hurricanes, that provides a risk score of 7.5, a medium-high risk. An impact score of 10 and a probability score of 1 to a GMD would provide a risk score of 5.5, a medium risk. This provides a mostly objective means of determining the risk of a specific hazard. There will, of course, remain an element of subjectivity in any assessment, based on the individual’s overall vulnerability to potential impacts. However, by assessing these risks as objectively as possible, one will be better able to prioritize them, which will be discussed more below.

Risk Assessment Resources

But how can one know what the probability and impact of these hazards might be in my area? There are multiple tools online to help determine risk in a specific area. Many of these are government sites, but are open to the public.

Probably the best resource for natural hazards is the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Storm Events Database. This site allows users to research specific events, down to the municipal level, dating back to 1950. By choosing a date range, state, county, and hazard, one can not only see a summary of those events within the county, but can also drill down on specific occurrences down to the municipal level, including the magnitude and impact of the events. Similar information for earthquakes can be obtained from the United States Geological Survey’s Earthquake Catalog. This site is more difficult to use, as the user will have to create a custom search for their area using the map tool under the “Geographic Region” header.

Information for technological hazards is a bit more difficult to obtain, however there are resources available. The Environmental Protection Agency’s website includes a page on the Toxic Release Inventory Program, which links to various tools that can provide information on potential and previous hazardous material issues in specific areas. State dam regulatory agencies will have information on potential dam breaches in a particular area.

State dam regulatory agencies will have information on potential dam breaches in a particular area.

Human-caused events, especially criminal and terrorist incidents, can be found on various law enforcement databases. Researching news articles on events in specific areas can also be helpful. As JWR has frequently stated, higher population density increases both the likelihood and potential impact of criminal and terrorist activity. However, both of those events can occur in rural areas, as well as urban. Remember, the purpose of a terrorist attack is not to generate casualties, but rather to create a psychological impact that can influence societal or political change. An attack on a rural target can have just as much of an impact, if not more, as an attack on an urban target.

Another potential source would be websites for local and state emergency management agencies. Often, these sites will have plans such as hazard mitigation plans available for public view, which can provide specific information on hazards within those areas. Local mitigation plans will contain a risk assessment of that specific area, which an individual can use, rather than going through the process of developing their own from scratch. As always when conducting research, consider the source. Triangulating, by using multiple sources to gather data for analysis, is generally a good idea.

Risk Prioritization

Once hazards have been identified and risks have been assessed, those risks should be prioritized. The simplest way to do this is to rank those risks and prioritize the ones with the highest scores. However, that may not necessarily be the best way to prioritize risk, particularly if one is operating in a resource-constrained environment. (Which, unless you’re Bill Gates, Elon Musk, or certain political bodies, would be almost everyone.) A bit of critical thinking may yield better results.

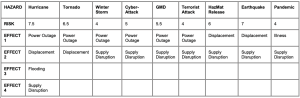

Many hazards share certain effects. For example, hurricanes, windstorms, tornadoes, cyber-attacks, winter storms, and GMD can all create power outages. By analyzing and identifying common effects of different hazards, one might better develop a better prioritization by focusing on those events with the most common effects. The table below provides an example of such an analysis. It should be emphasized that this table is an example only, and does not include all the potential hazards, nor does it include all of the potential effects of such hazards.

Based on this table, one can see that the two most common effects in this example are Supply Disruption, occurring in 7 out of 8 hazards and Power Outages, occurring in 6 out of 8 hazards. By focusing mitigation and preparation efforts on these specific effects, one can maximize the use of those limited resources.

Fire and Forget?

As one of my instructors in my Officer’s Basic Course used to say, “Time passes…weather changes…stuff happens”. It must be remembered that a risk assessment should be a living document. As conditions on the ground evolve, it may be necessary to revisit this analysis in order to address potential changes in probability and impact. A reasonable schedule for reevaluating risk would be to do so annually or after a major event or exercise (you are conducting drills and exercises, aren’t you?). This enables one to continually adjust preparation efforts as various risks change in accordance with developing conditions.

Conclusion

In closing, allow me to emphasize that prepping is very much a customizable experience. There is no one “right” way to do it (although there are a lot of wrong ways). Prepping efforts will depend on a wide variety of variables, including risk, vulnerabilities, capabilities, and many others. Assessing and prioritizing risk is an excellent way to begin this lifestyle (and it is a lifestyle, not a practice), since it allows one to better focus efforts and resources. More importantly, however, is to start moving forward. Assessments and plans are wonderful things, but unless they culminate in actions, they are ultimately worthless. May God bless you and yours as you endeavor to prepare for the coming — and present-day — troubles.