(Continued from Part 2. This part concludes the series.)

Pre-1899 Shotguns

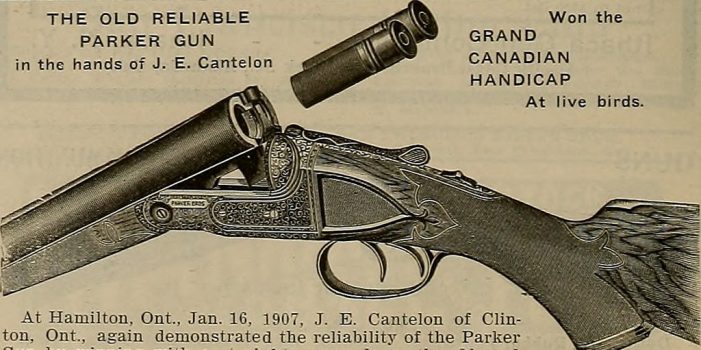

Shotguns from the late 1800s cartridge era are typically of a break-open design. There were pump action and lever action shotguns available such as those produced by Winchester, but they often command a high price. Old farm guns are easy to obtain and simple to work on. Often available online for under $300 or even as little as $100, they can be shipped to your door. Almost every hardware store in rural areas would have carried shotguns, and some even had their own locally produced models. This can make finding original parts a real chore.

One unique type of shotgun action is the trapdoor. Unlike the Trapdoor Springfield rifles that were an original design, the trapdoor shotgun is usually a conversion of an older muzzleloader such as an Enfield. They were often sold to native tribes in the United States and in Africa. I recently saw one of these at a local gun shop for an affordable price, was quite tempted to pick it up. I have also seen them on Gunbroker.com, often labeled as a “Zulu gun” or as a “Native shotgun” or “trade shotgun.” To repair these, you will need to be more familiar with muzzleloader parts than shotgun parts, as the only new part of the gun is the trapdoor and firing pin that were placed into the breech of the old muzzleloader. Springs will be of the type found in an Enfield muzzleloader, or whatever donor gun was used. While somewhat slower to load than other shotguns, a trapdoor conversion shotgun will do quite well for hunting, and is an interesting window into history.

Finding or Making Shotgun Parts

Like the trapdoor shotgun, break-open shotguns often share some things in common with traditional muzzleloaders. Many double barrel guns and some single barrel guns have a side-lock, rather than an internal hammer. The hammer is powered by a V-shaped leaf spring, and strikes a floating firing pin set into the receiver. This is a sturdy setup, but with three flaws. The leaf spring can break, the firing pin return spring can wear out, and the firing pin can become peened to the point that it does not function. While sometimes the main spring can be re-welded, it is better to replace it. Companies that specialize in muzzleloader parts will often have various sizes of springs for these locks, that can be filed to fit. Original shotgun parts often come up on auction sites in mixed lots for low prices. Buy several, and you can usually find one close enough to fit. The firing pin spring is an easy fix, similar to the firing pin spring issue in revolvers. Simply find a spring that matches at a local hardware store.

To make a new firing pin for a shotgun, I’ve used AR-15 firing pins as blanks. Some manuals that purport to explain how to fix or create “improvised firearms” will state that a screw or a nail can be used. This is NOT the case. You must use a very hard type of metal to create a firing pin. Not only will a softer material like a nail or a screw become unreliable, a firing pin that deforms easily will not have a constant length, and can become a safety hazard. Having several spare AR-15 firing pins around will ensure that you have proper stock for making your own. In the event that you need something larger, you can reduce the dimensions of a steel punch. Cut the punch down to size, and then file or turn it to the proper dimensions. The punch is hard enough to take the striking force of a shotgun’s hammer. This method has worked very well for me, most notable in an old Keystone Ejector 12 gauge. I made a new firing pin years ago, and the gun still serves as a “Critter Getter” out in my barn.

On break-open shotguns, one part that can fail is the locking spring, which keeps the barrel from opening up. Every time you press the lever to open the shotgun, you use the spring – it is a high-stress item. This was actually one of my first forays into gun repair, as I picked up an old Iver Johnson Champion 12 gauge when I was a teenager. I think I bought it at a garage sale for $25 because it had this issue. I went to the hardware store looking for a spring, and I settled on a piece of spring steel used in a window frame. I cut the metal to size with a hacksaw, heated it with a torch until I bent it to the proper angle, and then quenched it in water. Finally, I filed it to fit and drilled a hole for the set screw that keeps it in place. That gun was also missing its hammer spring, which I later found out was supposed to be a coil instead of a leaf. I stuffed a hardware store spring in there and used trial-and-error to make it fit – a method that also works for shotguns with internal hammers.

No discussion of antique shotguns is complete without a safety warning! Shotguns in the late 1800s were intended for use with black powder shells. Many had Damascus steel “twist” barrels, and some had shorter chambers such as 2.25” and 2.5” instead of our more common modern chamber lengths. Modern smokeless ammunition has a different pressure curve than black powder, and will likely rupture a Damascus steel barrel. Longer shells can also cause pressure issues. Unless you know the exact type and size of ammunition that your shotgun was intended to use, do not fire it. Don’t trust your buddy who insists that he has fired it before with Winchester shells that he bought from Wal-Mart. He might have gotten lucky–but you might not. There’s no need to take risks, as ammunition is available for older shotguns, and there are discussion boards on the internet where people exchange information about safely loading these weapons.

Info Resources on Pre-1899 Guns

No article can teach you everything you need to know about working on older guns. However, there are many excellent books, videos, and internet resources available. I will start by recommending TheHighRoad.org (THR) a truly excellent discussion forum for all things gun-related. You can lurk without registering and read the content, or join the community and ask any question you like. There are many members who are interested in muzzleloaders and older cartridge weapons. You might even meet some like-minded local people for networking and friendship. There are also weapon-specific forums for Swiss, British, and German rifles, as well as American guns such as the Trapdoor Springfield.

One video course that will undoubtedly be helpful is offered by the American Gunsmithing Institute (AGI). Among their vast video collection is the title “Making Coil and Flat Springs.” Robert Dunlap’s instructions will take you through everything you need to know about shaping, heat treating, and more. It is truly essential, as springs are going to be your most common problem. While you’re at it, check out the other metal work and refinishing videos, as well as the video on building a custom Mauser. There’s no end to what you can learn.

Several books have been helpful to me over the years, and some are getting harder to find. Older titles that are no longer published are frequently available through Amazon, which is where I obtained some of mine. While not especially related to antique guns, I recommend Andrew Dubino’s text Gunsmithing with Simple Hand Tools, and Ralph T. Walker’s Hobby Gunsmithing. Both books give good descriptions of how you can use hand tools and power tools in your shop to do customizing and fix common issues. Regarding ammunition, I recommend The Paper Jacket by Paul Matthew. Many rifle cartridges of the black powder era used paper-patched bullets. Recovering this lost art is an enthralling experience, and is essential to getting good accuracy from black powder rifles.

To conclude, now is the time to acquire the antique guns you want as well as the knowledge you need to make them usable. Purchase parts and materials while there is still time. Gain experience doing repairs, basic work, and enhance your marksmanship by shooting different weapons. Network with others and build relationships while you can. Find enjoyment in the history, and the pioneering spirit of doing things yourself.

Old hex keys (allen wrenches) are of a quality of steel good enough for firing pins, ideally turned on a lathe, but carefully hand ground will work. Note: don’t turn the steel blue when grinding, the heat treat will be ruined. You can also chuck in a drill press and work with a die grinder or dremel.

Aircraft supply houses such as Aircraft Spruce are a good source for small pieces of 4130 steel plate of sufficient strength for gun parts.

My grandfather was not trained as a gun smith, but he was a machinist. Interestingly he made some pocket money cleaning guns for the rich guys who didn’t want to do it. I learned much from him.

Very good article, with useful information. I concur regarding the Paul Matthews book, The Paper Jacket. It is excellent, and making paper patched bullets isn’t all that hard, though it is time-consuming.

Another fun topic to explore is black powder cartridge reloading. The rules are a bit different, but some of our current cartridges — such as the .45 Colt, .45-70, .303 British, and the .410 and 12 gauge — started with black powder. Hobbyists in BP cartridge loading tend to make some of their own supplies, such as lubricants, and many freely share their knowledge with others.

Drill rod is also used for firing pin base material needing to be machined or ground to dimension. Old break action single shot shotguns can have the extractor worn, or grooved by the firing pin, I have successfully TIG welded the worn groove with nickle rod and filed to fit like new.

I appreciate yesterday’s tip about the Mauser conversion.

I bought K98 parts gun for 40$ many years, intending to have it made over into a 30-06. Eventually I realized that it would cost more than it was worth to me. Turning the old clunk into a .45 bolt gun sounds like a fun project and a good beginner’s rifle after the heavy stock is cut down.