(Continued from Part 1.)

Goals and principles

A real-world example: The Shaolin monks

The origin story of the acrobatic kung fu the Shaolin monks practice is that it was developed for two reasons: Self-defense and general health. Meditation is a sedentary pursuit and the acrobatic kung fu allowed (and allows) them to pack in the flexibility, power, and cardiovascular training they needed to maintain health in a smaller frame of time. This is very much what we in the developed west face: a generally sedentary lifestyle that needs to be balanced with enough exercise to keep our general health up. Those of us who tend towards the prepping worldview tend to also have self-defense on our minds and that makes the Shaolin monks a worthwhile example to contemplate and imitate.

My goal with fitness: To be as useful as possible for as long as possible.

There are a lot of implications for that statement but I think it’s applicable for everyone. Specific training is king, if you practice a specific thing you become better at that specific thing. But, since none of us know exactly what’s in store, you can’t specifically train for what’s coming. This means I need to be useful as things are right now and as I think they may; and I need to recognize that my predictions may be wrong. I said it earlier I’ll repeat it here: general fitness that you will definitely need in all situations first (cardio, core, mobility), then specific fitness for which you foresee a need. So chew on it for a while, make your predictions, and then work so that you will be fit in what you think is coming.

In this article, I do not include specific benchmarks or goals. I know I’ve looked at various physical testing protocols and it is complicated question made more complicated by age and pre-existing conditions. I still want to know if I’m good enough. Am I where I ought to be? How do I stack up? In the book section of this article my top book has a good self-assessment included and that would be the one I would point you towards. If you want an Internet source, then Matt over at the Everyday Marksman has been putting a lot of thought into his physical assessment. I appreciate his engagement with the subject though he notes he is not an authority. Again though, I encourage you to think through what fitness abilities you predict you will need and build them.

I would caution everyone to be careful with any assessment. If you pass an assessment and injure yourself, you failed. Build your reserve first, especially if you’re running on or near empty.

My principles

- Part of my daily routine

- Balanced, to maximize utility and avoid injury

- Meaningful or enjoyable (ideally both)

A daily routine.

When I was first building my daily routine, I chose something relatively short and something that could be included as I advanced: core training. Every day, at the same point in the day, I went and did a short core routine. Eventually, that grew. I added short trainings after the core routine and those eventually grew until I was where I wanted to be time-wise in training. And I still start most days with a core routine before moving into the day’s exercise whether it’s mobility/yoga or strength/cardio, it starts with core. Slowly I built more. I highly suggest a short mobility or core routine as part of your daily routine especially to start. Unlike most training, your core can be trained daily and so can mobility. Chalk up the wins, create the habit, and then let it grow.

This doesn’t mean no rest days. Whatever routine you set yourself has to have rest days. Your body needs them in order to retain the fitness you are putting into it. I’ve used 5 on, 2 off. I’ve used 3 on 1 off. Some people use a 6 on and 1 off. You also need to know when to suspend training. I recently got through another round of Covid, wasn’t as bad as before but halting exercise when I still felt good but I knew it was coming (this time round I lost sense of smell) was the correct choice. I owe a medically trained brother for that piece of advice and I’m glad I followed it.

Daily routine means a sustainable level of exertion every day. Build up slowly. There’s a saying in fitness circles that “you just lapped everybody sitting on the sofa” and reminding yourself of that is probably a good thing. Especially those of us who remember being in good shape can push your body much harder than it can take. If you’re starting for the first time in a long time you can overdraw your fitness balance. You’ll do it at the time just fine. You might be able to do 80% of what you used to be able to do. The next day you’ll regret it. And your next workout will be a tiny percent of what you could do. Build. Slowly. This is the long haul.

The point about building slowly is even more important for those in non-sedentary jobs. You still need daily training but you have a different challenge. Because you are already stressing your body on a daily basis, and need to avoid injury more than the average person, you are going to need to build even more slowly. For you, starting with a 10-minute mobility workout may be the correct path. You need to add something that will not increase your injury risk and over time will give you the aspects of fitness your physical job doesn’t.

Balanced: to maximize utility and avoid injury.

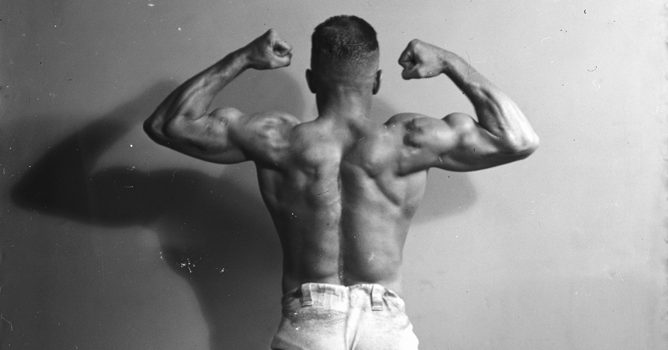

This means recognizing that your body moves as a system. You can take a bodybuilder’s approach of training specific muscle groups and that’s better than being sedentary but it doesn’t follow that you can do things like climbing over walls or carrying an awkward load. I like kettlebells, medicine balls, and olympic lifts because they involve your entire body moving under load. I like swimming, climbing and compound movements (sitouts and burpees) because you are training your entire body to do something. Make sure to include at least some compound movements in your training.

Balance also means making sure to train core, upper body, and lower body. It means balancing pushes and pulls, if you work the biceps (curls or chin-ups with the palms facing you), you need to work the triceps as well (close-in pushups or overhead extensions). You need to make sure you balance the opposed muscle groups. This approach also applies to stretching. With a complex muscle group like your shoulders it’s more complicated but the need to balance remains. Imbalance leads to injury.

Meaningful or enjoyable.

This commercial does an excellent job of showing at the end why the exercise was meaningful to the old man. This is an example of the work being meaningful even though it’s not enjoyable. Each bit of effort that he could more easily have avoided was worth it at the end. This is getting into Viktor Frankl territory: If our pain is meaningful, then we can bear it well. Keeping our goal in mind, the “why” behind the training is what makes it meaningful. Whether it is the ability to defend your family or the ability to teach your grandkids how to do something, if we tie the meaning to the action we can undertake it. This is especially important if circumstances restrict you to a path you don’t like.

If your joints mean you have to do water aerobics and you dislike it, your path is to focus on the meaning. Yeah, it may feel stupid but each session gets you closer to doing what you want to do. If you focus on the meaning the hard parts are easier to bear.

The other option is enjoyable. If you like doing the action, then you will do it. This is flipping Aristotle a bit. Aristotle held that virtue feels good to the virtuous. I am saying: “Choose a virtue that feels good so you become virtuous”. I like tossing my kettlebell around so I do it more often. I don’t proselytize on behalf of kettlebells, I don’t think they are necessarily better than other forms of strength training and cardio. I enjoy it and so it is better for me. If you enjoy rowing and hate ellipticals, that’s great. Do the rowing. If vice versa? Great. Use the elliptical. The differences between the various types of training may be real but the big difference is between training consistently and not training. Differences in training methodology and protocols pale when comparing consistent training to inconsistent training. So do what you like to do.

Ideally, your training is both meaningful and enjoyable. If you are more tactically minded you might like some of these types of training that mix obstacle courses with firearm competition. Or you might like obstacle courses (tough mudder and spartan are the two best-known brand names) because it’s a chance to test yourself against types of obstacles we don’t normally run into but may in a bad situation. Or maybe it’s orienteering challenges that are both meaningful and enjoyable. Rock climbing anyone? Virtual rowing competition? Martial arts training? There are many physical pursuits and you should be able to find one to suit. Also, keep an eye on the long term. What do you see yourself doing in your old age?

Look for something that is both meaningful and enjoyable but is at least one of those things. We do what we find meaningful or enjoyable. That is the core of your new habit of exercise. That is the reinforcement that will grow your fitness stockpile.

(To be concluded tomorrow, in Part 3.)