Back in 2018, during the comment period for the ATF’s “redefinition” (criminalization) of previously “ATF-approved” bump stocks, I wrote an article that was titled: The First Question is Always Jurisdiction. In the years since then, I’ve come to realize just how crucial it is to understand federal jurisdiction and to be ready to challenge it whenever the government strays outside of its constitutional fences.

It Started 90 Years Ago

Federal jurisdiction became grossly over-applied in the early 1930s, as the Prohibition Era was nearing its end. With the passage of the National Firearms Act of 1934 (enforced by the Treasury Department), Federal policing increased. As the Great Depression deepened, a huge list of “Alphabet Soup” agencies was launched by Congress. Many of these three-letter agencies brought with them new Federal policing powers. Consequently, this broadened both the power and frequency of use of federal courts. More courts and more convictions of course meant building and staffing more federal prisons.

With the end of Prohibition in 1933, new perceived threats were created: marijuana and narcotics. Decades later, the DEA was established. Meanwhile, the FBI grew in power. The IRS developed a burgeoning enforcement arm. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) began referring more cases for prosecution. Eventually, the National Park Services, Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and even the EPA got into the act. More and more federal agents began carrying badges and pistols.

Today, there are no less than 51 federal law enforcement agencies, and at least 200 more federal agencies that have more limited law enforcement authority. There are more than 3,000 codified federal crimes, with more added every year. Presently, there are 142,441 federal inmates in Bureau of Prisons (BOP) custody. The conviction rate for Federal criminal courts is astoundingly high. Only about 2% of federal criminal defendants go to trial — 97% accept plea bargain convictions. The Pew Research Center tabulated that of the 79,704 defendants who were under federal charges in 2018, only 320 received acquittals in trials. There were convictions in 99.96% of all other cases referred by the U.S. Attorney’s Office. Of the acquittals, judges acquitted 38% of the defendants in the cases that they decided. But juries only handed down acquittals in 14% of their trials.

One key aspect of jurisprudence in the United States is the distinction between State and Federal jurisdictions. Federal jurisdiction is based on Article III of the Constitution and The Judiciary Act of 1789. Case law delineating Federal jurisdiction distinction dates back to the cornerstone Marbury v. Madison, Swift v. Tyson, and Erie Railroad v. Tompkins decisions.

Not Just Assumed

Contrary to popular belief, federal jurisdiction cannot be just assumed, “because it’s the law.” Jurisdiction must be first established. But oddly, federal jurisdiction is only rarely challenged. Properly, it should be challenged long before any case goes to trial. But it can be challenged at any time — even on appeal of a conviction. To wit:

Once Federal Jurisdiction has been challenged, it must be proven. Main v. Thiboutot, 100 S. Ct. 2502 (1980).

Jurisdiction can be challenged at any time, even on final determination. Basso V. Utah Power & Light Co., 495 2nd 906 at 910. Also see: Marciela Reyes v. Carehouse Healthcare Center LLC etal., 2017 WL 2869499 (C.D. Cal. July 5, 2017).

The Constitution’s Article III provides Federal jurisdiction over suits between citizens of different states. This is commonly called Diversity Jurisdiction, and it is codified in U.S.C. Section 1332. Originally (per The Judiciary Act of 1789), the threshold was $500. But by 1988, it was raised to $50,000.

The Wicked Wickard Decision

You may be wondering how we collectively got into this predicament. A lot of it can be traced to just one decision that was handed down in 1942: Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U.S. 111.

I won’t go through the minutiae of describing the Marbury v. Madison, Swift v. Tyson, and Erie Railroad v. Tompkins decisions. Suffice it to say that Federal power steadily grew, especially during and after the 1861-1865 Civil War. But I must focus on the 1942 Wickard v. Filburn decision, because it typifies federal government arrogance and over-reach.

Wickard v. Filburn must be one of the Supreme Court’s worst and most statist decisions. Caroline Fredrickson, a Visiting Professor at Georgetown University Law Center co-authored a case summary that includes this:

“During the Great Depression, Congress passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938, a law regulating the production of wheat in an attempt to stabilize the economy and the nation’s food supply. In particular, this law set limits on the amount of wheat that farmers could grow on their own farms. Roscoe Filburn, a farmer, sued Claude Wickard, the Secretary of Agriculture, when he was penalized for violating the statute. Filburn argued that the amount of wheat that he produced in excess of the quota was for his personal use (e.g., feeding his own animals), not commerce (e.g., selling it on the market), and therefore could not be constitutionally regulated. The Court upheld the law, explaining that Congress could use its Commerce Power to regulate such activity because, even if Filburn’s actions had only a minimal impact on commerce, the aggregated effect of an individual farmer’s wheat-growing exerted a substantial economic effect on interstate commerce. In terms of the Constitution, this holding offered a broad reading of Congress’s power under the Commerce Clause.”

Let me clarify: The Supreme Court found that farmer Filburn growing grain on his own farm and feeding it to his own cows indirectly affected interstate commerce because of this twisted logic: By growing his own grain, it was argued that Roscoe Filburn wouldn’t be buying a comparable amount of grain elsewhere, and presumably some of that grain might come from out of state. If that absurd logic were applied in other “commerce”, then virtually any transaction of buying or selling anything in any state by any individual could be deemed to have an “economic effect on interstate commerce” and thus be considered “interstate commerce” — placing it under federal jurisdiction! What a tangled web we weave…

It bears mention that the Wickard v. Filburn decision was handed down during the global chaos of the Second World War by a court that was dominated by liberal Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) “New Deal” appointees during his most unusual 12 years in office. Aside from George Washington, no President selected more men to sit on the Supreme Court than FDR. Those appointments had huge, long-lasting effects. Two of FDR’s appointees were among the longest-serving justices: Hugo Black and William Douglas served on the court for 34 and 36 years, respectively.

Peak Government

The 1940s can be seen as the “peak government” years, worldwide. Totalitarianism was the order of the day. And we must admit that we had our own form of it here, complete with a huge draft, confiscation of gold, and internment camps for Japanese Americans. But we didn’t call it totalitarian — perhaps because the American variety wasn’t quite so bad as that experienced in Nazi Germany, fascist Italy, imperial Japan, or the communist Soviet Union. We just kept on saying: “It’s a free country” — and we somehow did so with a straight face. I must also point out that under FDR’s leadership, the US. allied itself with Stalin’s brutal USSR, by employing the classic “The enemy of our enemy is our friend” logic. That set us up for the Cold War and a massive thermonuclear arms race.

Ever since the FDR days, the real focus of federal criminal jurisdiction has been in three key areas: taxes, drugs, and guns. Ironically, all three of those have quite flimsy federal nexus. In fact, those three should all be state-level issues, but they have been made federal during the early 20th Century. In recent years, about half of the 50 states have legalized marijuana — either medically or recreationally. Yet, anachronistically, possession of “the herb” remains a federal crime.

The Roots of Unconstitutional Gun Laws

All Federal gun law authority is based on the Commerce Clause. The government claims authority because of interstate commerce. But most recently, the ATF has begun claiming authority over intrastate (in-state) commerce, leaning on bad case law, like Wickard v. Filburn and Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council. (So-called Chevron deference.) The ATF’s most recent proposed rulemaking grossly expands the definition of “engaged in the business.” In effect, they want to put all gun sales under Federal jurisdiction and run the sales of any post-1898 guns through FFLs, complete with filling out Form 4473s and FBI background checks.

Given the recent Bruen decision and the upcoming Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo decision (that will almost surely end Chevron deference), there is no way that the ATF’s absurd redefinition of “engaged in the business” can pass constitutional muster. An intrastate sale of a used gun between two private parties who are residents of the same state is not interstate commerce!

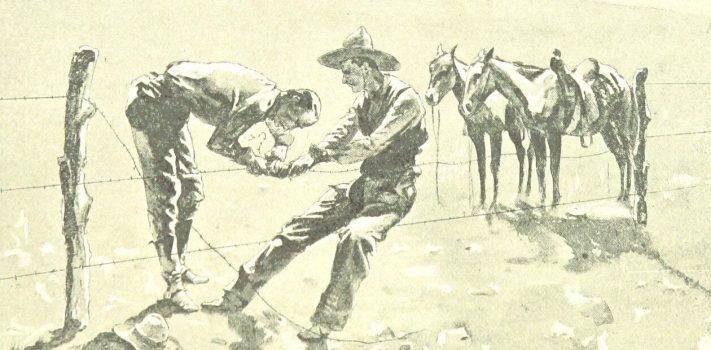

Fence It In!

What is needed is for the Supreme Court to overturn the insanely statist Wickard v. Filburn decision and reduce the scope of what constitutes interstate commerce. The court came close to this in United States v. Alfonso D. Lopez, Jr., 514 U.S. 549 (1995) a landmark case that struck down the Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990 for exceeding federal power to regulate interstate commerce. But sadly the court did not go far enough in fencing in Congress and the executive branch. Perhaps with Raimondo, the courts will finally get it right!

They should then declare both the National Firearms Act of 1934 and the Gun Control Act of 1968 unconstitutional.

The Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo case was argued before the Supreme Court in January, 2024. A decision is expected sometime in the next few months. With that decision now so imminent, it is important to ponder how American jurisprudence got to its present sorry state.

And if it is decided correctly, the pending CRPA v. Luna case will also set a very valuable precedent, based on the Constitution’s Privileges and Immunities Clause. The Luna case will make concealed carry recognized much like driving a car, out of state. You cannot be denied a fundamental constitutional right, just because you cross state lines.

I am confident that the now more conservative Supreme Court will continue to reaffirm the Bill of Rights, including the 10 Amendment. The Federal government needs to be reined in!

As an aside, I should mention that while Federal jurisdiction is generally over-used in the 21st century, it can indeed be useful in some cases involving personal liberty. Deprivation of rights by local and state officials can be raised as an issue under 42 USC Section 1983. Far too many bully police officers — at all levels, local, state, and Federal — have been hiding behind Qualified Immunity for too long. They need to face justice and change their policies.

In Closing

In the 20th century, one common retort in combative conversations, arguments, and personal accusations was: “Don’t make a federal case out of it!” We need to take that to heart. All too often, Federal cases are made when no jurisdiction properly exists. – JWR

For some further reading, I recommend the book Federal Jurisdiction, by Erwin Chemerinsky.