In 2007, I began warning SurvivalBlog readers about global over-reliance on Just-In-Time (JIT) inventory management. This system — also called lean inventory management or kanban — was first developed by Toyota in Japan, in the 1950s. There, with largely internal chains of supply that were all clustered around the major cities on Japan’s largest island, Honshu, the kanban system worked with wonderful efficiency. Kanban soon branched out to the other three primary islands: Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku. Manufacturers were able to cut costs by keeping their parts inventory small, and placing frequent orders to their supplying wholesalers and component parts makers. Kanban became very popular in Japan in the 1960s.

The Japanese lean inventory way of doing business was so successful that it caught the attention of American and European efficiency experts. They soon adopted it, preferring to use the term Just-In-Time (JIT). The bean counters earned nice Christmas bonuses, and both CEOs and shareholders were happy with a fatter bottom line. By the late 1990s, in many industries JIT became the norm. Even in worldwide trade, kanban proved to be efficient, if allowances were made for the lag time created by transoceanic shipping. American companies also found lean inventory beneficial in states with outdated inventory taxes.

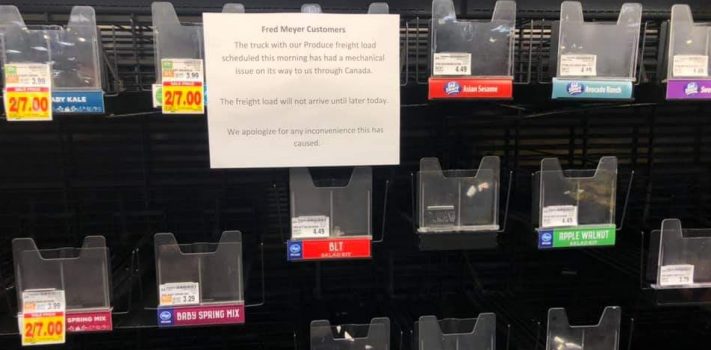

Seeing the success of JIT in industry, wholesalers and retailers emulated kanban practices. This widespread adoption was seen most dramatically in supermarkets. Most new stores that were built after the early 1990s omitted having a large rear storeroom for “overstock”. What you see on the shelves is all that they have available in the store. Increasingly, it is route drivers and jobbers from third party companies that actually stock supermarket shelves. This started first with bread shelves, but now entire swaths of store shelves are stocked by people who are not store employees. This shelf-stocking activity largely goes on between 2 AM and 6 AM every morning, so most customers are oblivious to this hum of activity.

A Well-Oiled Machine

In normal times, the Just-In-Time (JIT)/kanban way of doing business works beautifully. It is a daily ballet of delivery trucks, bar codes, QR codes, and automatic re-ordering database systems. Companies like UPS, DHL, and FedEx have made billions of dollars doing their part of the complicated daily dance routine. Everything hums along nicely, with nary a hiccup. The bottles of vitamin pills that you buy are wonderfully fresh, because they just came off the packaging line a couple of weeks ago instead of being six months to a year old. There is very little waste, “idle stock”, up and down the supply chain.

Manufacturing managers grin and say: “Let the guys up the chain carry the expensive inventory. I need less shelf space, and when I do physical inventory shelf checks, it is quick and easy. I run a lean machine.”

Companies win awards for Six Sigma process controls that embrace JIT. By keeping things as lean as possible, there is great efficiency. And then consequently there are tidy annual bonuses. For most companies, kanban is a “win-win”, and everybody is happy. There are even national JIT and Six Sigma conventions, where experts deliver white papers on squeezing the last iota of efficiency out of manufacturing, transport, distribution, and retailing. The conventioneers schmooze and congratulate each other. They’ve then gone back to their Fortune 500 companies, fancying themselves kaizen gurus, and made plans to get “even more lean.” American-style kanban has been fine-tuned for 25 years.

The kanban way of manufacturing and commerce works marvelously, all up until the day that it doesn’t. We are now experiencing The Day. Sadly, Der Tag arrived within weeks after companies in China’s Wuhan province began having production glitches. Two years in, the global supply chain crisis is worsening. Many of the production gaps from many months ago still haven’t yet worked their way through the system. We are witnessing a train wreck in slow motion. Mainstream news broadcasters proclaim a “broken global supply chain”, and wonder how we got into this mess. But some of us had seen Der Tag coming, for a long time.

Missing Ships and Missing Chips

Just one example of the breakdown of the supply chain can be seen in the production of cars and trucks from Detroit’s Big Three manufacturers. A car, truck, tractor, or ATV can be 99% complete, but still unable to be delivered to dealership for lack of just one integrated circuit (IC) microchip. No chip, and no shipment. Car and truck dealerships across the U.S. and Canada have mostly empty lots. Meanwhile, countless acres of lots in Michigan are piling up with 99% complete vehicles. Our Editor at Large Michael Z. Williamson spotted this news story that shows the extent of the problem.

At last report, some manufacturer lots are full, and new cars are even being lined up on the shoulders of rural highways, and even the Kentucky Speedway. The new vehicle shortage at the dealership level has spilled over into the used car, truck, and RV market. For the past six months, some used vehicles with low mileage have been selling at prices higher than the sticker price of a new vehicle!

The chain reaction effects of a broken supply chain can be clearly seen at transoceanic shipping terminals. Continental Express (CONEX) shipping containers are now horribly delayed getting processed through ports. Empty CONEXes are piling up in some places, but in short supply, in others. Warehouse space is running short. Ships sit at anchor or automated stationkeeping, awaiting their turn to unload at major seaports. In the biggest American ports, the queue to get a berth at a CONEX terminal now stretches beyond 70 days. That represents untold man-hours and gallons of fuel. So it is no wonder that the cost to ship a CONEX across the Pacific Ocean has increased dramatically. Before the Wu Flu pandemic, this would have been unheard of. Now, at ports like San Diego and Long Beach, it is “the new normal”.

Time to Reassess

I’m hopeful that the end result of the current supply chain crisis will be a somber re-evaluation of kanban practices. Clearly, supply chains must be shortened, more domestic production must be emphasized, and greater resiliency must be created. A key part of that resiliency must come in the form of deeper stockage of parts at the manufacturer level. Also, inventory taxes should be abolished.

If America’s manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers fail to learn this lesson, then they are doomed to repeat it. And if this were to happen in the midst of a world war, then the results could be monumental and strategically decisive. – JWR