Bottom Line, Up Front

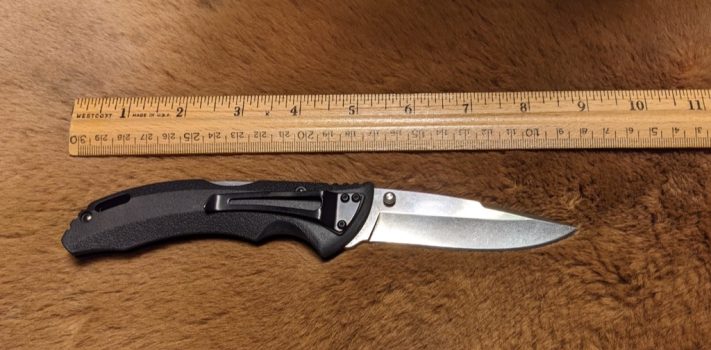

The Buck 286 Bantam BHW Folder is a robust, 3.38 inch, drop-point-blade knife. It comes out of the box razor sharp. The thick, nicely-textured, fiberglass-reinforced-nylon (FRN) handle is just a little on the chunky side for everyday carry (EDC), but is unusually comfortable under heavy use. It has dual thumb studs for ambidextrous one-handed opening. The stonewashed finish on the 420 HC blade is attractive. The lockback holds the blade securely open. With a manufacturer-suggested retail price of $33.99 at the time of this writing, and widely available online for less, the Bantam represents excellent value for the money, especially for an American-made knife.

First Impressions

The knife arrived appropriately packaged in a paperboard box. The box effectively protected the knife and provided helpful information printed on the outside without wasting excessive resources on packaging.

The most beautiful words on the box were “Knife Made in the USA”. I am extremely impressed that Buck Knives is able to make such high quality knives in the United States at prices that are competitive with knives produced overseas using slave labor. Most Buck brand knives are now made in Idaho.

I was less impressed with the words “Forever Warranty”. Reading the fine print revealed that the “Forever Warranty” does not cover normal wear and tear. I can understand a “Forever Warranty” not covering abuse and misuse of a product. But when I read the words “Forever Warranty” I expect it to cover more than just defects in material or workmanship. So I feel a little letdown. I feel that the words “Limited Warranty” or even “Limited Lifetime Warranty” are more properly descriptive of what Buck covers.

The blade is made out of 420 HC steel. This in itself is not especially impressive, since 420 HC is generally considered to be a budget stainless blade steel. But Buck has a reputation for drawing out the fullest potential of 420 HC. This is due to the Paul Bos heat treatment process. It involves heating, super-freezing, and then reheating the steel. This allows the blade to take and hold an edge better than is generally possible when using 420 HC. The end result is that Buck Knives customers receive more for less.

The blade is made out of 420 HC steel. This in itself is not especially impressive, since 420 HC is generally considered to be a budget stainless blade steel. But Buck has a reputation for drawing out the fullest potential of 420 HC. This is due to the Paul Bos heat treatment process. It involves heating, super-freezing, and then reheating the steel. This allows the blade to take and hold an edge better than is generally possible when using 420 HC. The end result is that Buck Knives customers receive more for less.

The pocket clip was a little lighter gauge of steel than I expected, but it held up extremely well throughout the testing period.

There is no metal frame inside the somewhat chunky FRN handle. The extra FRN in the handle compensates for the missing metal while making the knife lighter and less expensive than a knife with a metal frame. I am not yet sure what impact the lack of a metal frame will have on the long-term durability of the knife over many years of use.

There is no metal frame inside the somewhat chunky FRN handle. The extra FRN in the handle compensates for the missing metal while making the knife lighter and less expensive than a knife with a metal frame. I am not yet sure what impact the lack of a metal frame will have on the long-term durability of the knife over many years of use.

The lanyard hole is larger than average, being roomy enough to accommodate even a 0.5-inch nylon strap. This is helpful, since many lanyard holes on many other knives are too small to be of practical use. The lockback was solid, but was somewhat difficult to disengage. It gradually improved over the course of the testing period, but was still a little stiff even after more than a month of regular use. It is likely that it will smooth out even more with continued use.

The lanyard hole is larger than average, being roomy enough to accommodate even a 0.5-inch nylon strap. This is helpful, since many lanyard holes on many other knives are too small to be of practical use. The lockback was solid, but was somewhat difficult to disengage. It gradually improved over the course of the testing period, but was still a little stiff even after more than a month of regular use. It is likely that it will smooth out even more with continued use.

Testing

I carried the knife for more than a month, and used it for a host of the mundane tasks of everyday life. These tasks included, but were not limited to, the following:

∙ Opening boxes, envelopes, and other packages. This is the most frequent use of my EDC knife.

∙ Cutting packaging away from a toy that I was opening for my grandchildren.

∙ Opening a bundle of sandbags.

∙ Cutting twine to re-bundle the sandbags that remained after I filled the ones I needed.

∙ Making wood shavings to help kindle a camp fire to make s’mores for the grandchildren. The knife really excelled at this task. It is razor sharp, and the beefy handle was comfortable and easy to grip as I cut the hard, kiln-dried wood.

∙ Cutting a strip of bicycle inner tube to make a band to secure the handle of a roof rake when the rake is disassembled.

∙ Removing fired cartridge casings from the chamber of a single-shot derringer (while wearing gloves) that does not have an extractor.

∙ Cutting plastic packaging and tape from a roll of poultry netting.

∙ Cutting open the dog’s monthly dose of flea and tick treatment.

∙ Peeling an old shipping label from a box that would be reused.

∙ Chopping spruce needles and plantain weed leaves to add to an infusion during the process of making homemade aftershave.

∙ Chopping spruce needles and plantain weed leaves to add to an infusion during the process of making homemade aftershave.

∙ Peeling away a shipping label that was obscuring directions printed on the outside of a box.

∙ Prying out the orifice reducer from a bottle of aftershave in order to allow the bottle to be refilled.

∙ Cutting open a bag of dog food.

∙ Cutting open the packaging on a new pair of scope rings.

∙ Opening packages of water bottles so that the bottles could be distributed to the participants in a pro-life march.

∙ After the pro-life march was over, cutting caution tape off of poles that had helped define parking areas during the march.

∙ Cutting open boxes of borax and washing soda to use in making homemade laundry soap.

∙ Cutting down a box to fit an item that needed to be returned to a vendor.

Biometric Befuddlement

I also used the knife to open a new tube of grease for a grease gun. In the process, I got some grease on the blade. I used a paper towel to clean the blade. While cleaning the blade, I got a little careless, and cut the index finger on my left hand.

The wound was not terribly deep. I washed the wound with soap and warm water, dried it thoroughly, glued it shut with super glue, and covered it with a Nexcare waterproof bandage.

The biggest impact of the incident was biometric. I use my left index finger to unlock my cell phone and also to open a handgun vault that I am testing. Those devices obviously could not read my fingerprint through a bandage. But even after the bandage was removed, it took a number of days for my finger to heal well enough for the scanners to recognize it. The fingerprint scanner on the phone did a better job than the scanner on the handgun vault. The scanner on the phone could begin to recognize the fingerprint after several days of healing. After more than ten days of healing, the fingerprint scanner on the handgun vault still failed to recognize the marred fingerprint about half the time.

This incident provided a good practical lesson on the dangers of over-reliance on technology. Fortunately I had other methods of accessing both my phone and the handgun vault.

Buck Knife History

The history of Buck Knives begins with a 10-year-old blacksmith apprentice in Kansas in 1899. That precocious young apprentice, Hoyt H. Buck, soon developed a new method of heat-treating the steel used in hoes, knives and other tools.

By the time he was 18 years old, Hoyt abandoned blacksmithing and sought greener pastures in the Pacific Northwest. There he met and married his wife, started a family, and worked in the lumber industry.

Decades passed, life went on, and things changed. By the late 1930s, Hoyt was living in Mountain Home, Idaho, where he became the pastor of an Assembly of God Church.

When World War II came along, Hoyt heard about the need for knives for the United States armed forces. He bought a forge, anvil, and grinding mandrel, and resumed blacksmithing, setting up a shop in the basement of his church. There he began making knives for the servicemen at Mountain Home Army Air Corps Base.

With the end of the war and reduced activity at the Air Corps Base, the economy in Mountain Home, Idaho declined dramatically. Hoyt and his wife traveled to San Diego, California, where they moved in with their oldest son, Al. Al had become a bus driver in San Diego after serving with the Coast Guard there.

Hoyt continued his knife-making in San Diego, and eventually prevailed upon Al to join him in the business. A few years later Hoyt passed away. By then, Al had mastered the art of knife making.

In the early 1960s, Buck Knives introduced a new product, the 110 folding hunting knife. It rapidly became one of the most popular knives ever made, with 15 million units produced since 1964, not counting the millions of imitations and knock-offs made by other companies.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Conclusions

In my opinion, Buck offers some of the best values in American-made knives. The 286 Bantam BHW is one of the many fine choices that Buck offers. It is sharp, attractive, and reasonably priced. If you are looking for a budget-friendly option for an EDC knife, the Buck 286 Bantam BHW would be an excellent choice.

Disclaimers

I did not receive any financial or other inducement to mention any vendor, product, or service in this article.

JWR Adds: Without Tom’s knowledge, Buck Knives became a Survival Affiliate Advertiser after he had written this review article, but before it was posted. SurvivalBlog earns a modest commission on sales of products sold by our affiliate advertisers if readers use an affiliate link to reach a company web site and then [place and order.